Texas Hidden History: GLO StoryMaps

Texans have long turned to the Texas General Land Office (GLO) for maps and other tools used to display and organize information about the state’s rich natural resources. Since 2014, one such GLO initiative is Texas Hidden History (THH), a collaborative project between the GLO’s Archives and Records and Geospatial Technology Services Team. In 2020 the initiative was expanded to use Esri GIS software to produce narrative StoryMaps on Texas History topics that align with GLO collections strengths. Explore our StoryMaps below.

From Soil to Oil: Texas Geology and Cartography, Nineteenth Century – Present

The Texas General Land Office (GLO) Archives holds thousands of historical maps that cover many topics, including the geology of Texas. Many geological maps first informed potential settlers of the composition of the soil in Texas. Years later, as railroads moved across the United States, geological maps guided the railways’ path towards firm stable ground. As geology’s focus turned to minerals, oil, and natural gas in the twentieth century, geological maps helped the state raise money for the Permanent School Fund by leasing the rights to these valuable natural resources.

This StoryMap is inspired by an exhibit at the GLO Archives in 2024-2025. Using GLO maps, it examines how cartographers produced maps depicting this data as geologists refined their study of Texas and the American West. An interactive dashboard explores the geology of Texas as well as rocks and minerals that GLO staff have collected from state-owned lands.

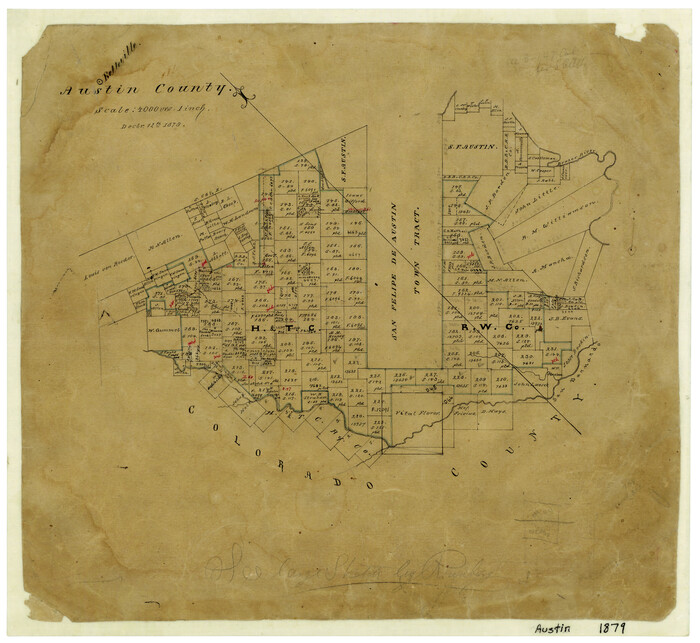

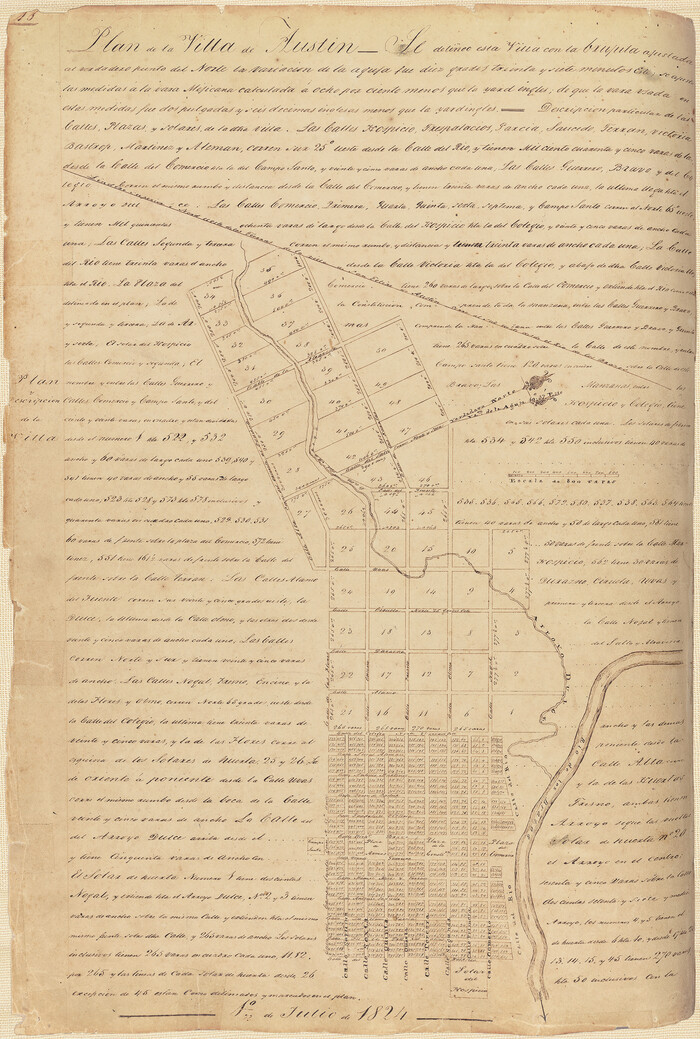

Best Laid Plat: San Felipe de Austin in Vision and Reality, 1823-1836

Mexican colonization laws of the 1820s empowered empresarios such as Stephen F. Austin to create new towns for immigrants, who were expected to adapt their cultural and civic traditions to Mexican standards. The town of San Felipe de Austin, which was surveyed by Seth Ingram between October 1823 and July 1824, provides a vivid example of this effort. Envisioned as a central hub of Austin’s colonization project, the new town was also designed to meet Mexican urban specifications. The survey plat of San Felipe, originally drawn by Ingram to Austin's specifications, now exists only in the GLO's Spanish Collection. It represents a fascinating blueprint for the process of hybridization.

For various reasons, the town envisioned in Ingram’s plat never materialized. Though San Felipe could boast some modest successes by 1830, Anglo settlement patterns, geographic factors, and political instability stunted the town in its infancy. This StoryMap analyzes Ingram’s plat of San Felipe as a product of a unique experiment in frontier urban planning. Using original sources from the GLO and other repositories, it situates Ingram’s survey plat in the context of the Mexican municipal tradition, revisits the history of the town’s founding, and employs GIS mapping to explore the hybrid vision behind the plat’s creation. Finally, it analyzes the growing gap between Austin and Ingram’s vision and the complicated reality of colonial settlement, a disjuncture that ultimately doomed San Felipe and Mexican Texas as a whole.

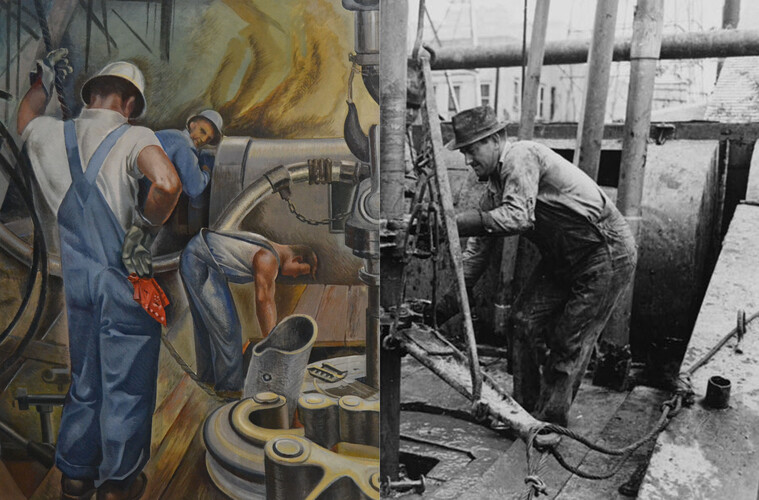

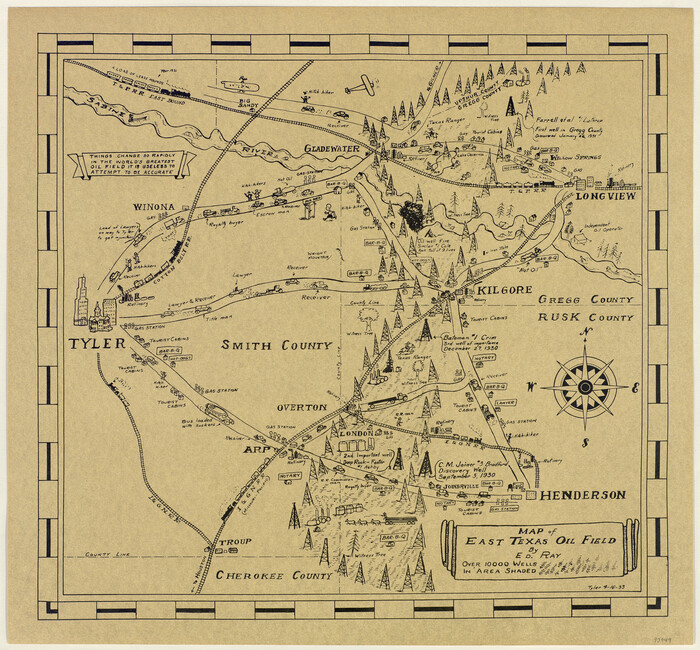

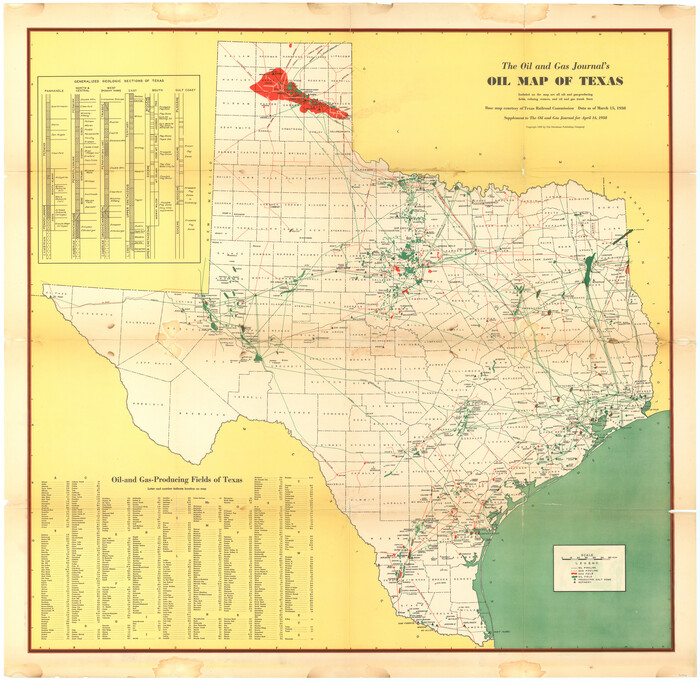

The Booming Great Depression: Inside the East Texas Oil Field, 1930-1945

Like the rest of the United States, Texas in the 1930s struggled in the throes of the Great Depression. Thousands of men sought work or other financial opportunities. An especially attractive area of the Texas economy during this bleak period was the oil and gas industry, and in particular, the oil boom taking place in northeast Texas. Although primarily an agricultural state, the discovery of oil at Spindletop in 1901 had set off a decades-long scramble to find other drilling sites. One of the most important was the East Texas Oil Field, discovered in early September 1930 by Marion “Dad” Joiner at the No. 3 Daisy Bradford well west of Henderson. The resulting oil boom transformed the five East Texas counties of Cherokee, Gregg, Rusk, Smith, and Upshur, but its importance did not end there.

This StoryMap explores the first fifteen years of the East Texas Oil Field's tumultuous history, from 1930 to 1945, and highlights the significant impact the oil boom had on regional, state, and national affairs. Using maps held by the Texas General Land Office (GLO) Archives, and photographs and other print material from the era, it showcases the dramatic economic, demographic, social, and cultural transformations that took place in this corner of East Texas.

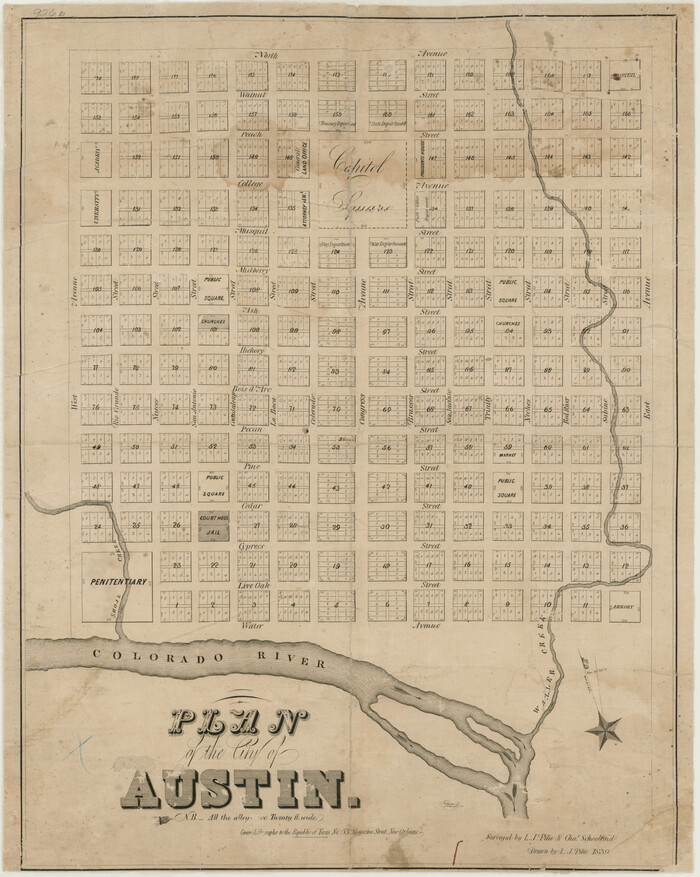

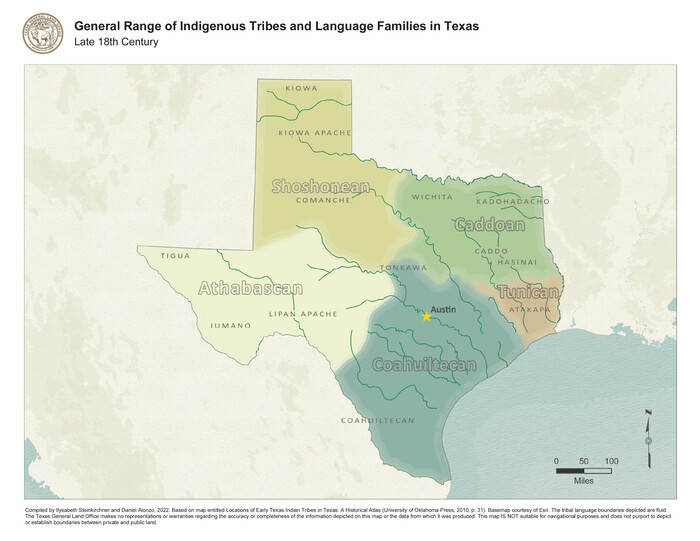

Capitalized: The Many Capitals of Texas and the Ascent of Austin

There were many capital cities in the land now known as Texas. Before colonization, many tribal nations ranged over the area for thousands of years. Colonizers established capital cities in the ever-changing boundaries of Spanish Texas. The Republic of Mexico and then the Republic of Texas established competing capital cities through revolution. After Texas gained its independence from Mexico, the young republic scouted for a new capital city. In 1839, Waterloo was renamed Austin and declared the capital of the Republic of Texas. At the time, however, it was anything but certain that the designation would be permanent.

This StoryMap travels the winding path that began in 1682 with the first capital city of Spanish Texas and ended when Austin officially became the last and permanent capital of Texas. Along the way, many capital cities were named and settled; some endured, many more were abandoned.

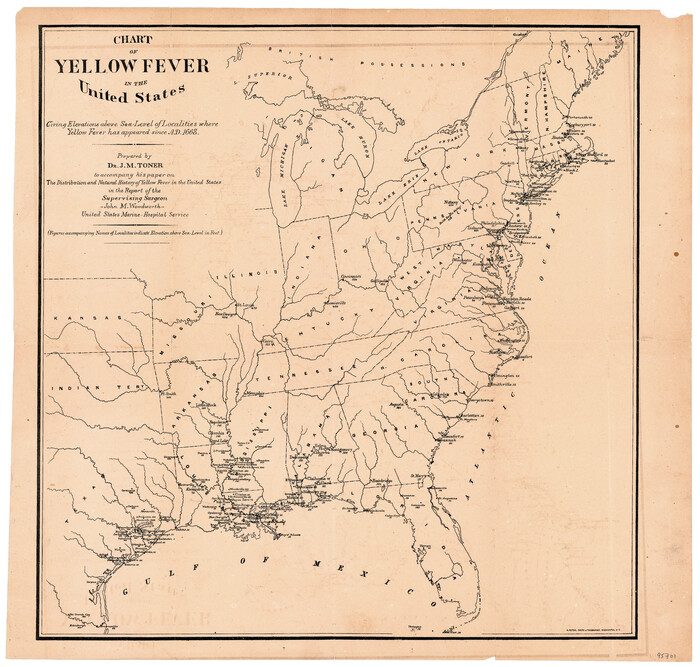

Plague of the South: Yellow Fever Turmoil in Texas, 1839-1905

In the nineteenth century, the dreaded yellow fever haunted Texans with sickness and horrific death until its final epidemic in 1905. Beginning in 1839, it plagued much of the South almost every summer. A whisper of the disease nearby could cause panic, forcing thousands to flee to uninfected places. The mysterious disease, the vector for which was not discovered until 1900, earned the name "yellow fever" because it caused liver failure and jaundice (yellowing of the skin).

This StoryMap follows key outbreaks in Galveston and other Texas cities from 1839 to 1905. Interactive maps of the disease’s spread across Texas and land use changes related to public health in Galveston, chart yellow fever’s progression across the state and efforts taken to contain the disease. Taken together, this project demonstrates the impacts of yellow fever on Texas: exacerbating racial and class divides, inflaming municipal rivalries, invading military encampments during both the U.S.-Mexico War and the American Civil War , and disrupting tourism and economic output until new sanitation measures and medical breakthroughs emerged at the close of the nineteenth century.

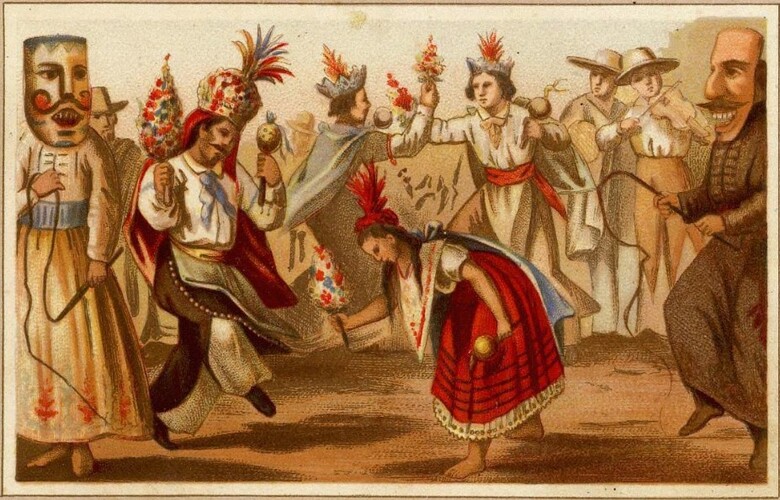

Mapping Cross-Cultural Encounters in Early Texas

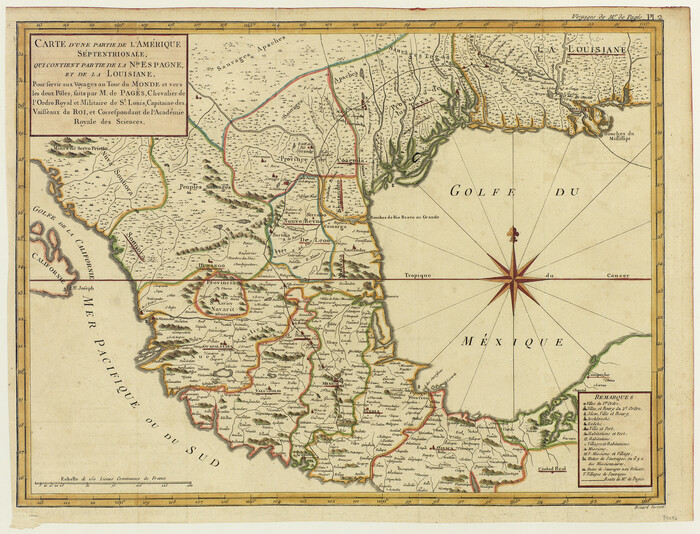

In June 1767, Officer Pierre Marie François de Pagès left his post with the French Navy in Saint-Domingue (now Haiti and the Dominican Republic) and set out on a journey around the globe. This event led to the publication of one of the earliest traveler's accounts of New Spain, including parts of present-day Texas. Published in 1782, de Pagès' Voyages Autour Du Monde offered European readers a rare glimpse of Spanish North America, a place long shrouded in imperial secrecy.

Taking de Pagès' map and travelogue as a starting point, this project retraces the Frenchman’s route through New Spain; and it contextualizes his observations with images, maps, and primary source materials from the Texas General Land Office and other archival repositories. Though flawed and culturally biased, de Pagès' work provides an intriguing portrait of life in several Texas towns in the late Spanish period. It also offers us a chance to reexamine Texas' position as a cultural crossroads between Spanish, French, and Indigenous societies at a time of significant geopolitical upheaval.

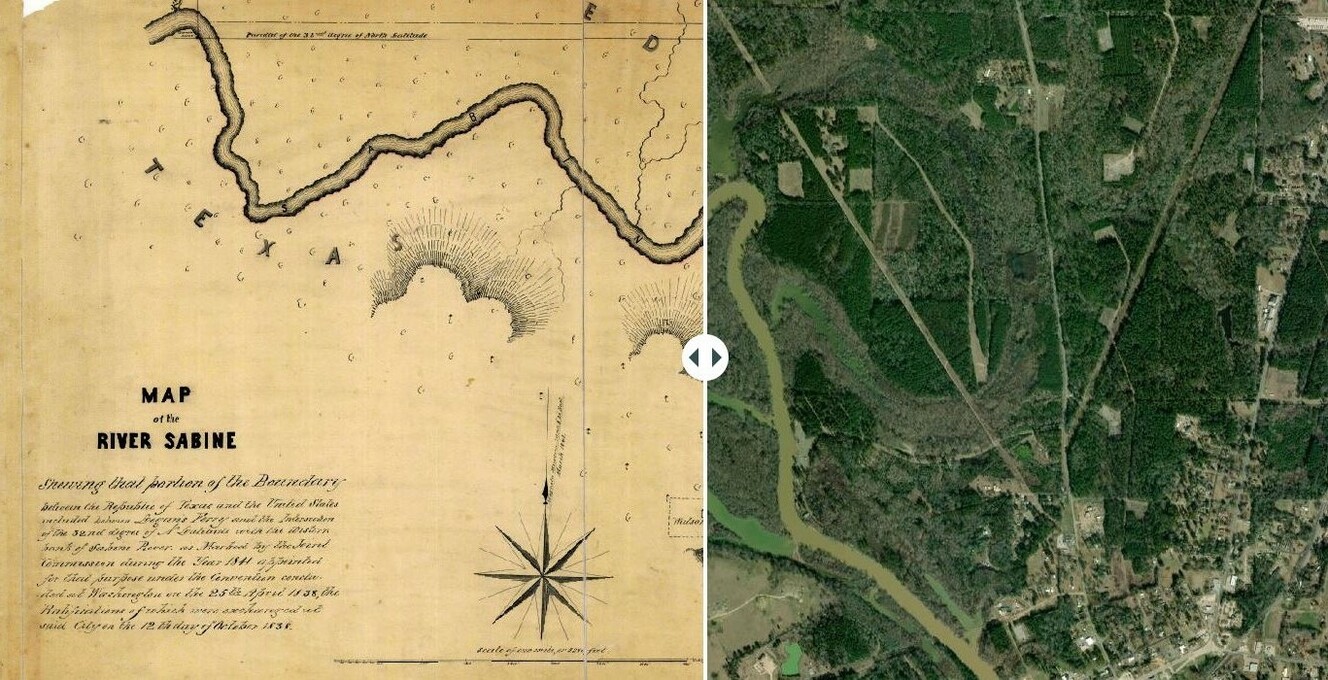

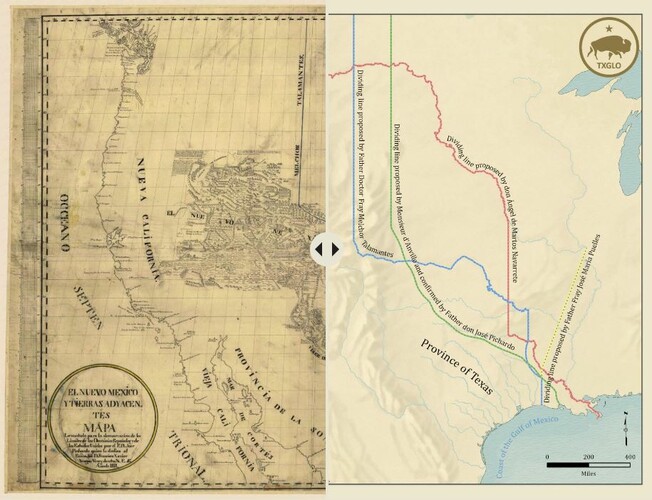

Tracing the Sabine River: The History of Texas' Eastern Boundary

In 1840, Colonel Robert Potter faced a problem. Originally from North Carolina, and more recently, a signer of the Texas Declaration of Independence and veteran of the Battle of San Jacinto, he had just been elected a senator to the Congress of the Republic of Texas. Despite his and his constituents’ confidence that he was in fact a resident of Texas, surveys in the neighboring state of Louisiana disagreed. Not until the following year, when surveyors of the Joint Boundary Commission between the Republic of Texas and the United States finally reached the marshy lands around Caddo Lake, straddling Texas and Louisiana, was his Texas residency confirmed.

How was Colonel Potter’s residency in doubt? This StoryMap traces the history of Texas’ easterly boundary stretching along the Sabine River to the Red River, and positions three agreements as key to the establishment of this border. These agreements – the 1803 Louisiana Purchase, 1819 Adams-Onís Treaty, and 1838 Convention of Limits – encouraged powers to finally identify a clear boundary, establish a formal agreement, and ultimately survey the land from the Gulf of Mexico to the Red River. Further, as agreements were negotiated, re-negotiated, and challenged until the boundary survey was completed in 1841, the chronology that follows demonstrates that boundaries are far from natural. Instead, with maps used as key tools in wielding this power, they are shaped, contested, and ultimately set by people.

Mission Lands into Private Hands: Secularization and the Transformation of San Antonio de Bexar, 1794-1831

In the late eighteenth century, Spanish reformers moved to dissolve the iconic Franciscan missions of San Antonio, which they considered to have outlived their usefulness. With few neophytes (Indigenous converts) left at the missions and a more challenging evangelization field beckoning elsewhere, the Franciscan friars agreed to relinquish control and turn the mission communities over to civilian leaders and secular (diocesan) priests, distributing mission land and assets to the remaining residents. This process, known as “secularization,” proved complicated and proceeded slowly—it was only completed under the auspices of the independent Mexican republic around 1831. Its ultimate impacts, though, were far-reaching.

This StoryMap explores the theological and political underpinnings of mission secularization and traces its practical impacts on San Antonio society between the 1790s and the 1830s. It draws on the rich trove of mission records held in the GLO’s Spanish Collection and historic maps from its Map Collection, along with other Texas history repositories. Taking Mission San Francisco de la Espada as a case study, the final section uses GIS technology to visualize the fragmentation of mission properties and assess the local outcomes of the process.

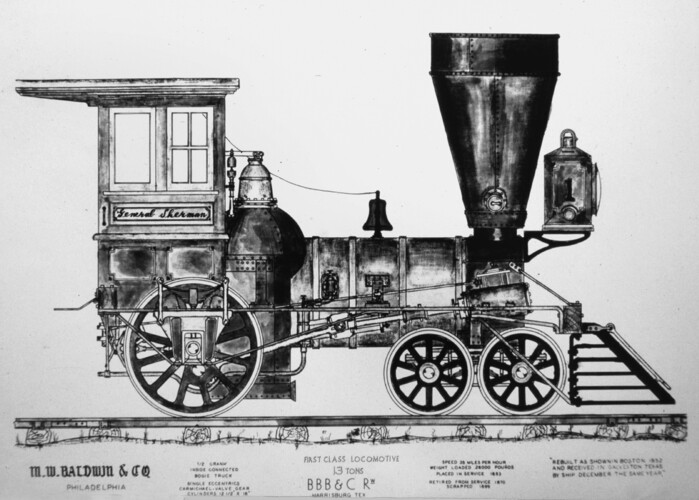

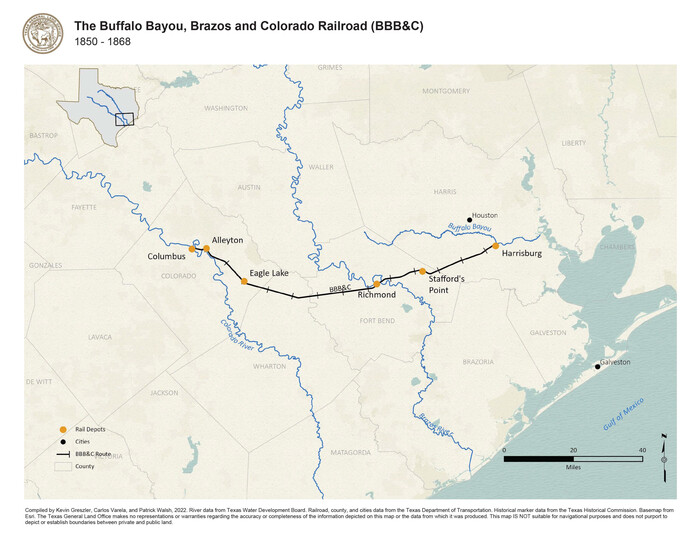

The Iron Horse Reaches Texas: The Buffalo Bayou, Brazos and Colorado Railroad

Decades passed between the chartering of the first railroad in the United States in 1827 and the arrival of the “iron horse” to Texas in 1853. Using an innovative public land-for-rail program to overcome inadequate financing options, the state of Texas, through the General Land Office, helped facilitate the construction of an early rail network. As Texas progressed through the republic, antebellum, and Reconstruction eras, motivation for railroad development changed.

This project shows how Texas’ first railroad, the Buffalo Bayou, Brazos and Colorado, laid the foundation for a transportation network that forever transformed the state’s infrastructure, economy, and population.

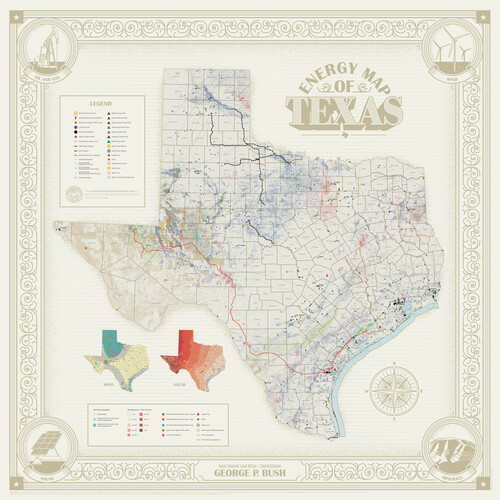

Energy Map of Texas

This StoryMap portrays Texas as the historic and future energy leader of the world and provides an all-of-the-above approach to managing energy resources on state-owned land.

Related records

Mapa topográfico de la provincia de Texas

1822

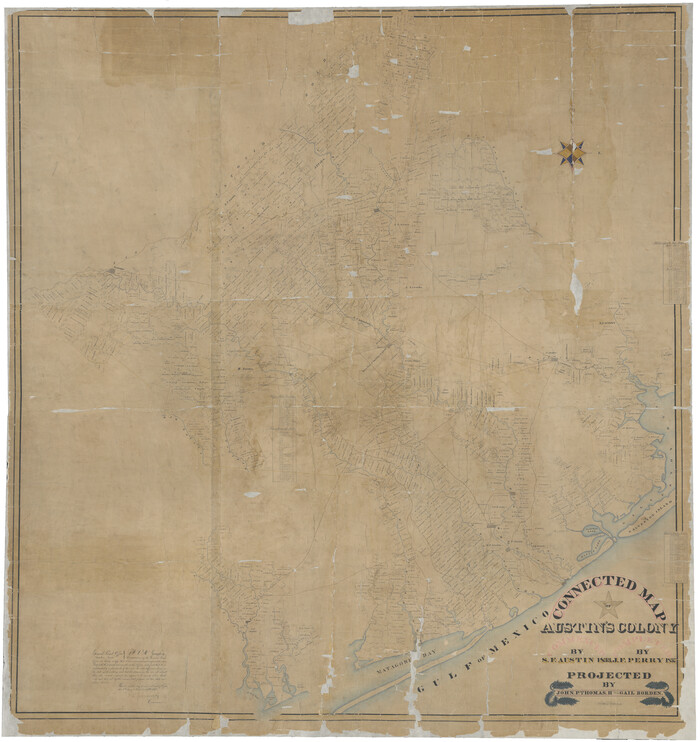

Connected Map of Austin's Colony

1837

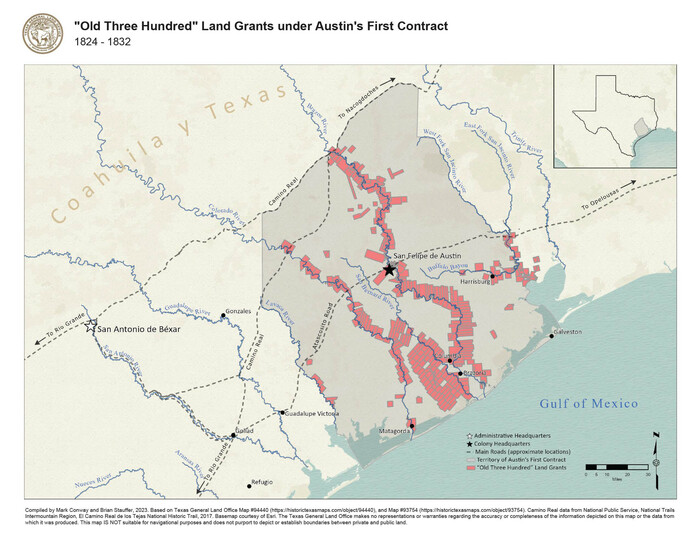

"Old Three Hundred" Land Grants under Austin's First Contract

2023

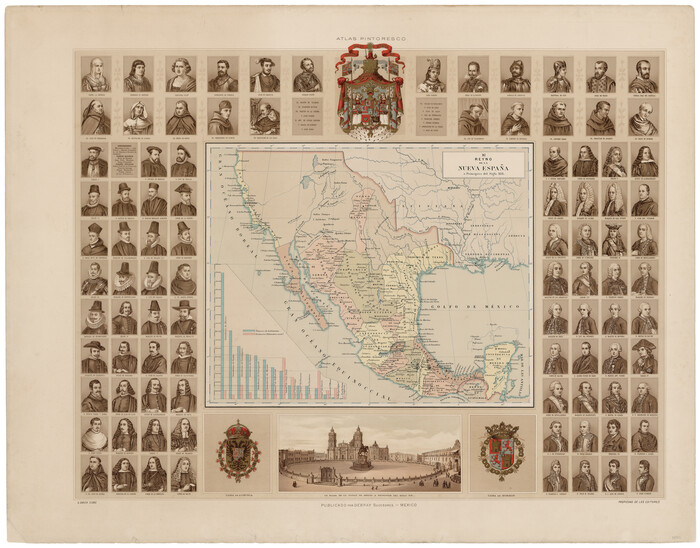

Reyno de la Nueva España a Principios del Siglo XIX

1885

Land grants from the state of Tamaulipas in the trans-Nueces

2009

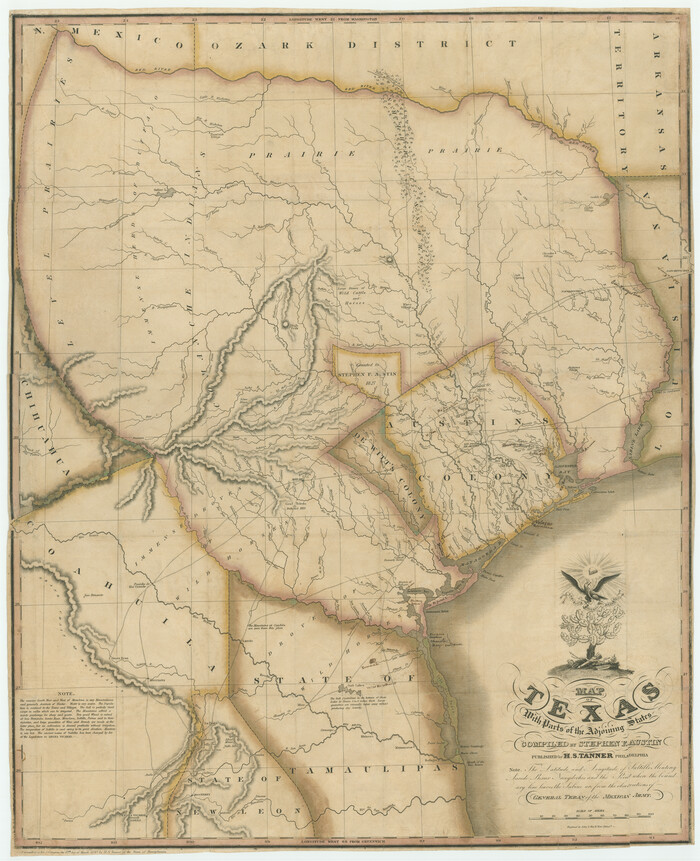

Mapa de Texas con partes de los Estados Adyacentes

1832

Minutes of the Ayuntamiento of San Felipe de Austin Vol. 1

Minutes of the Ayuntamiento of San Felipe de Austin Vol. 3

Map of Texas with parts of the Adjoining States

1830

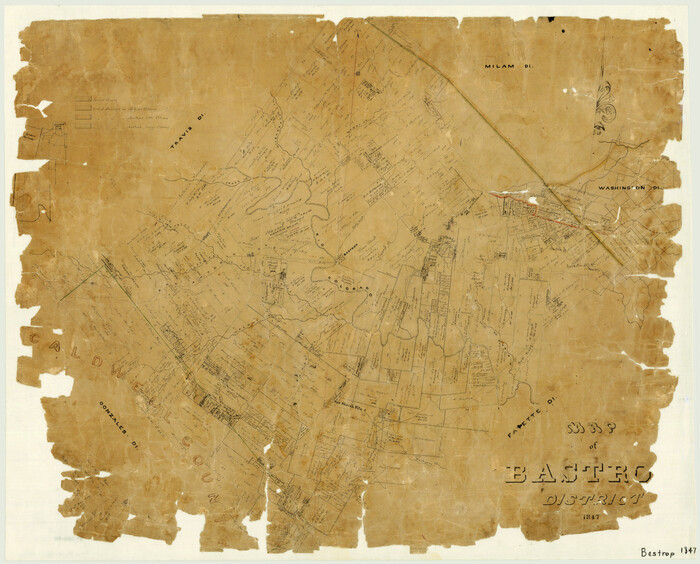

Map of Bastrop District

1847

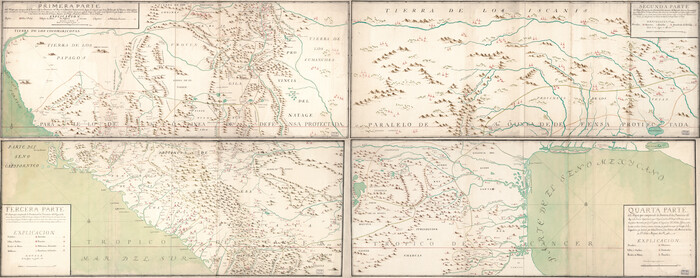

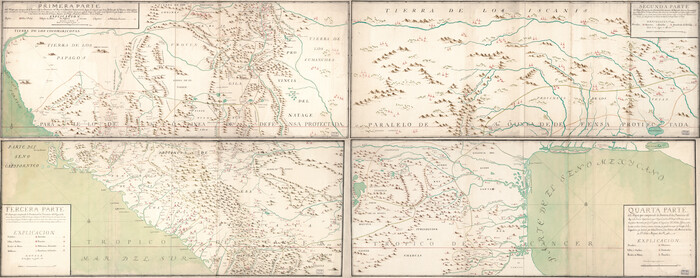

Mapa que comprende la Frontera de los Dominios del Rey, en la America Septentrional, segun el original que hizo D. Joseph de Urrutia, sobre varios puntos observados por él, y el Capitan de Yngenieros D. Nicolas Lafora

1769

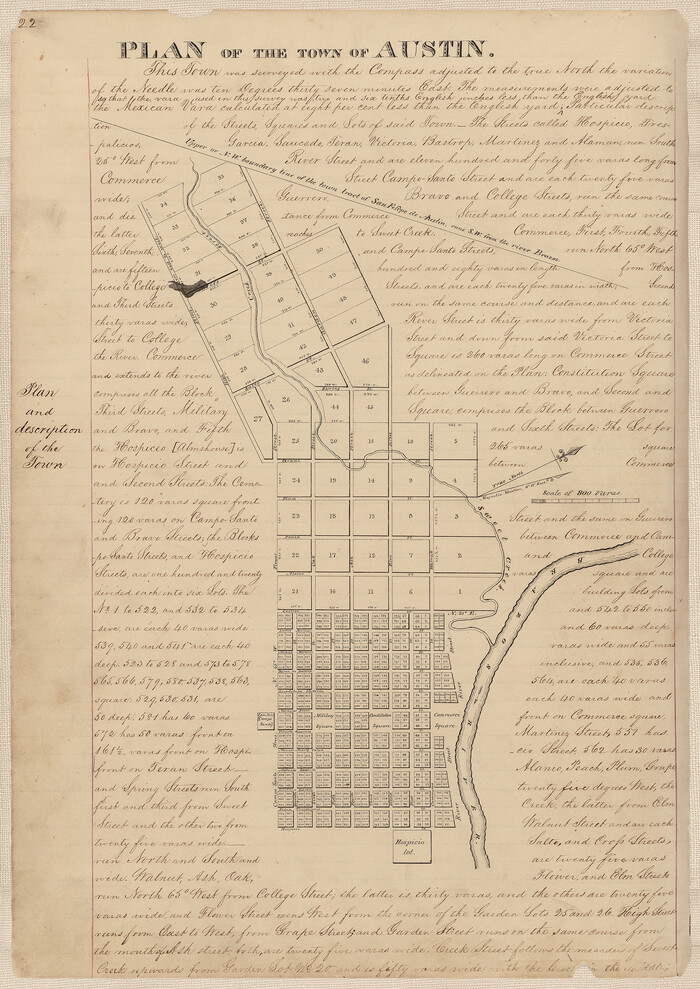

Plan de la Villa de Austin

1828

Plan of the town of Austin

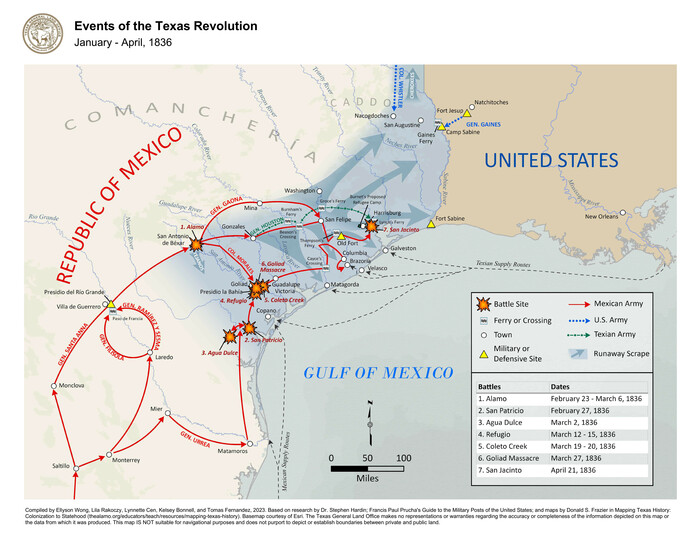

Events of the Texas Revolution

2023

Map of East Texas Oil Field

1933

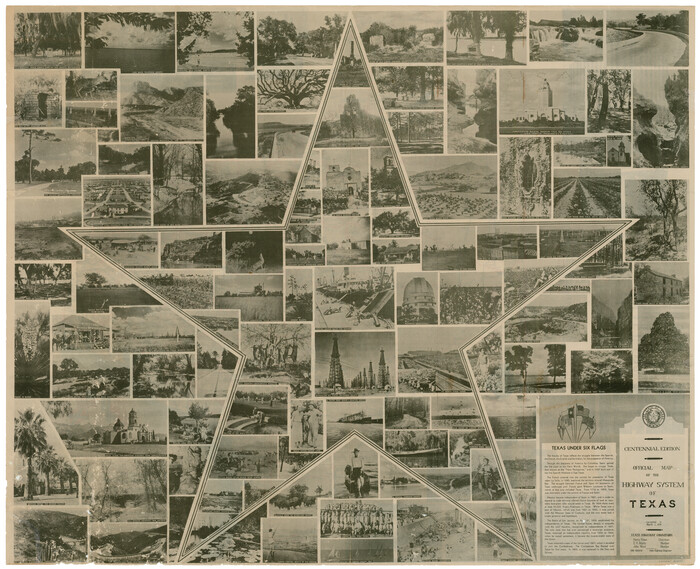

Official Map of the Highway System of Texas

1936

The Oil and Gas Journal's Oil Map of Texas

1938

City of Austin and Vicinity

1839

Plan of the City of Austin

1839

General Range of Indigenous Tribes and Language Families in Texas

2022

Chart of Yellow Fever in the United States

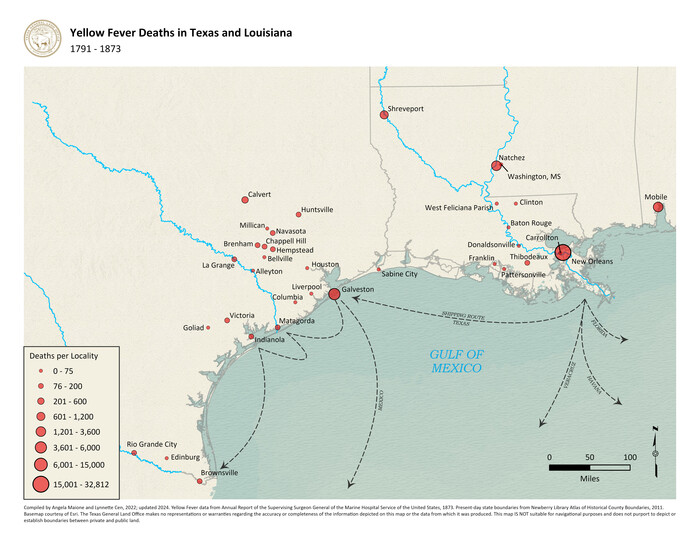

Yellow Fever Deaths in Texas and Louisiana

2022

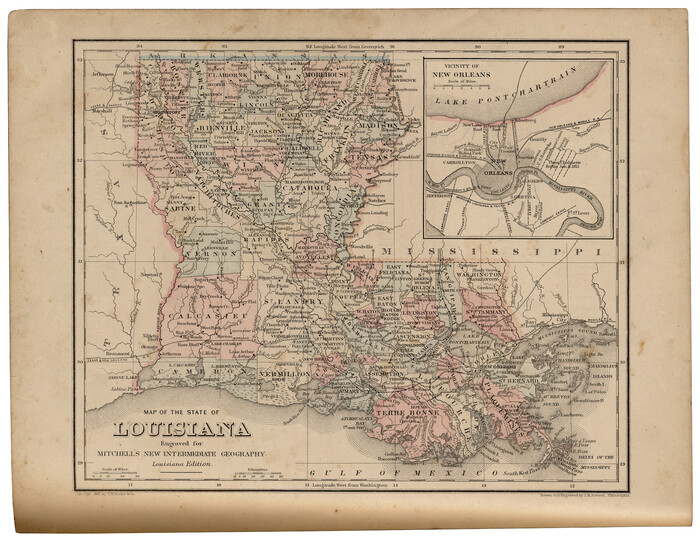

Map of the State of Louisiana engraved for Mitchell's new intermediate geography, Louisiana Edition (Inset: Vicinity of New Orleans)

1885

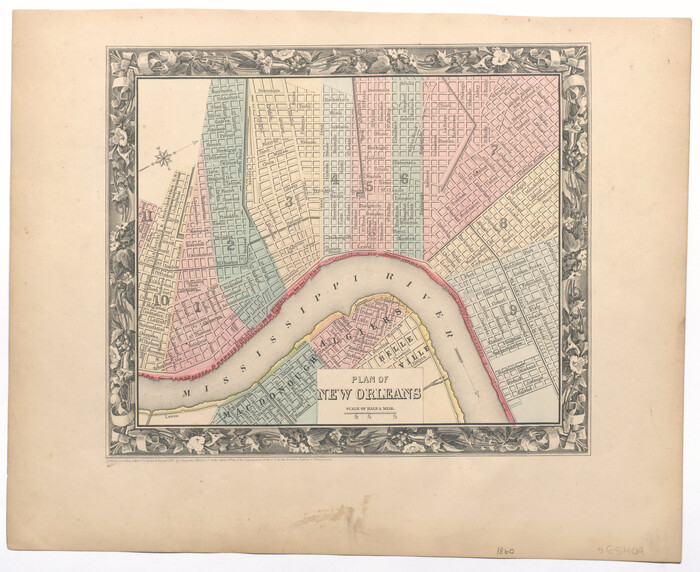

Plan of New Orleans

1860

Carte d'une partie de l'Amérique Séptentrionale, qui contient partie de la Nle. Espagne, et de la Louisiane

1782

Mapa que comprende la Frontera de los Dominios del Rey, en la America Septentrional, segun el original que hizo D. Joseph de Urrutia, sobre varios puntos observados por él, y el Capitan de Yngenieros D. Nicolas Lafora

1769

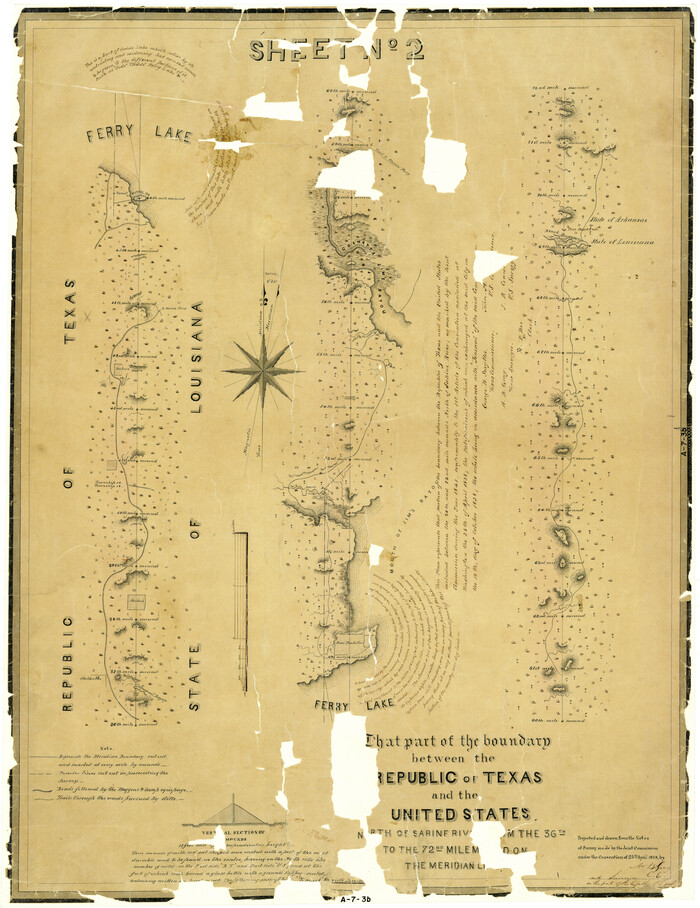

That part of the boundary between the Republic of Texas and the United States, North of Sabine River from the 36th to the 72nd Mile Mound on the Meridian Line (Sheet No. 2)

1842

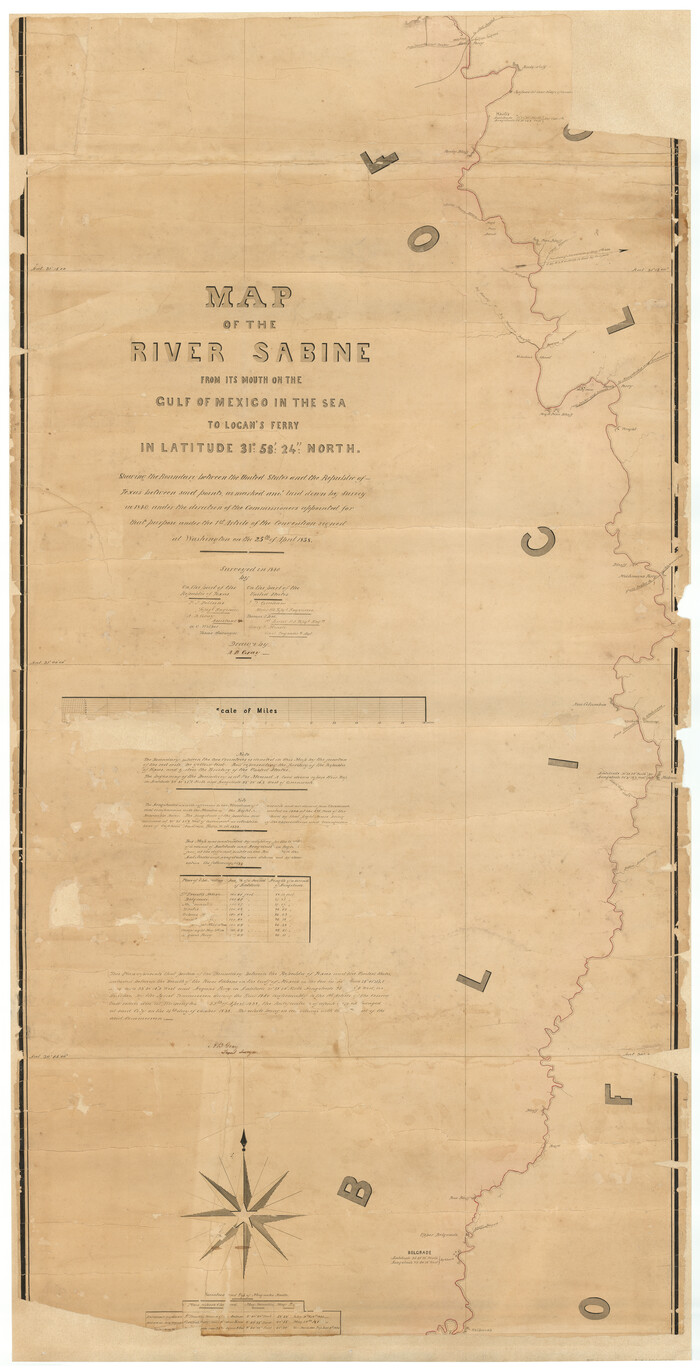

Map of the River Sabine from its mouth on the Gulf of Mexico in the Sea to Logan's Ferry in Latitude 31°58'24" North

1842

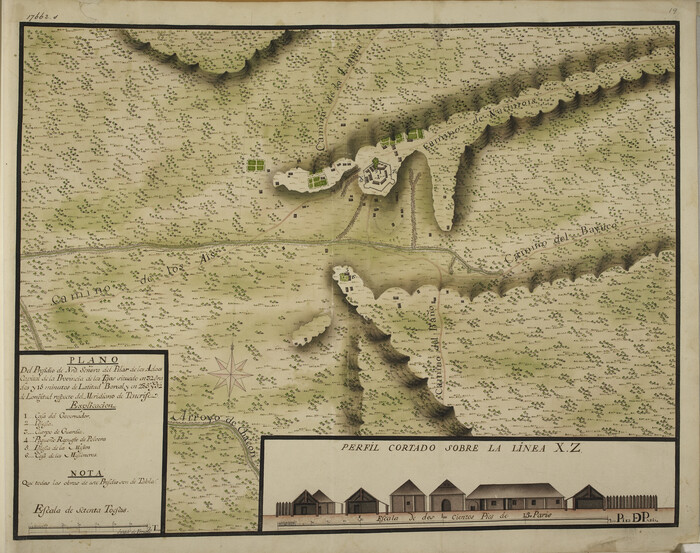

Plano del Presidio de Nra. Senora del Pilar de los Adaes, Capital de la Provincia de los Tejas situado en 32 grados y 15 minutos de Latitud Boreal, y en 285° y 52' de Longitud respecto del Meridiano de Tenerife

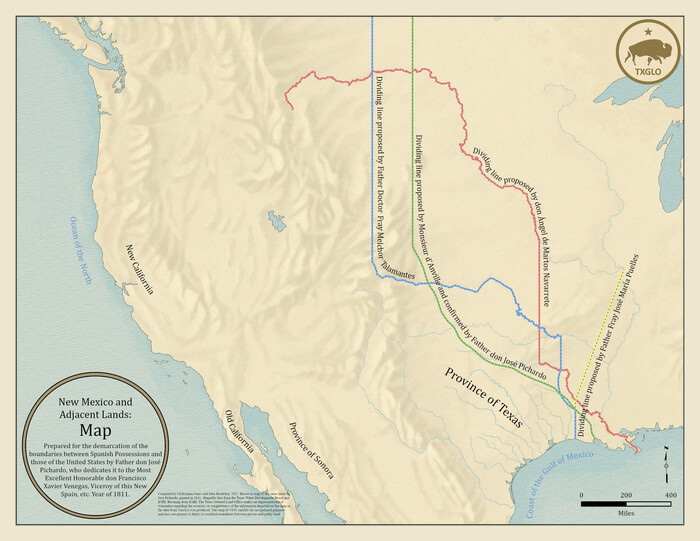

New Mexico and Adjacent Lands

2022

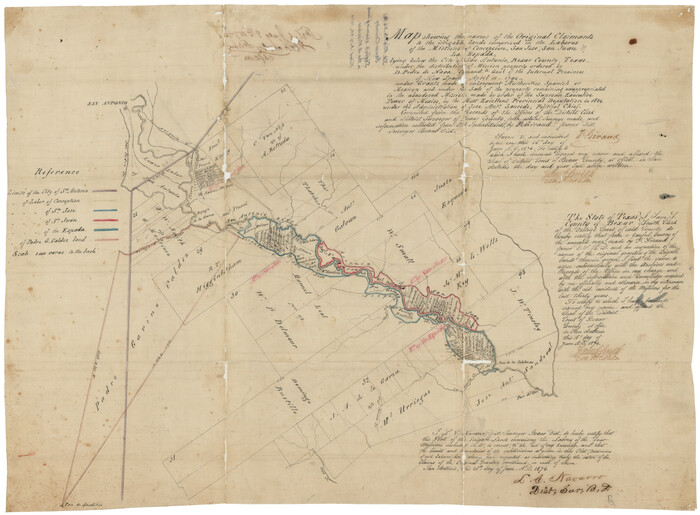

Bexar County Sketch File 36c

1874

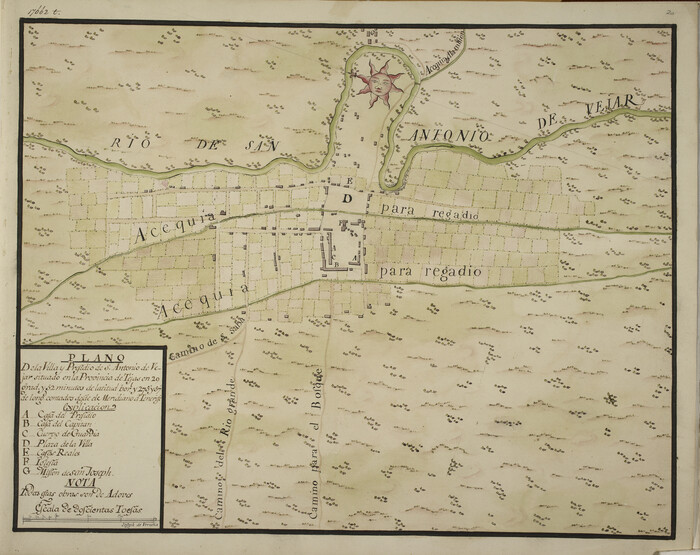

Plano de la Villa y Presidio de S. Antonio de Vejar situado en la Provincia de Tejas en 29 grad. y 52 minutos de latitud bor. y 275° y 57' de long. contados desde de Meridiano d. Tenerife

1768

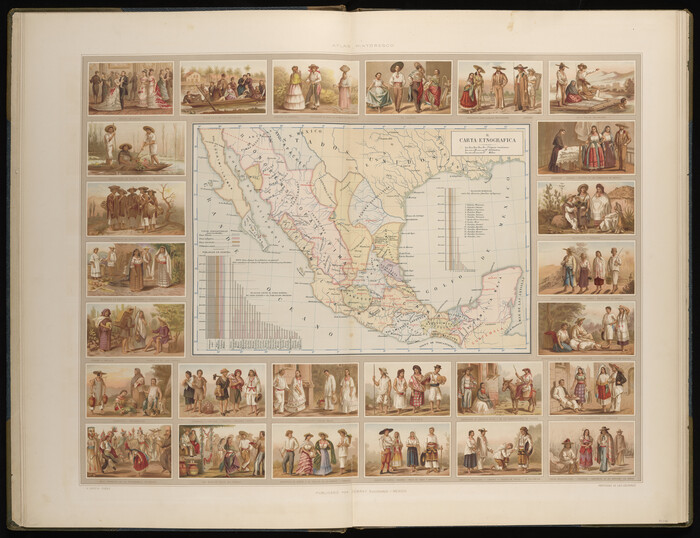

Carta Etnografica

1897

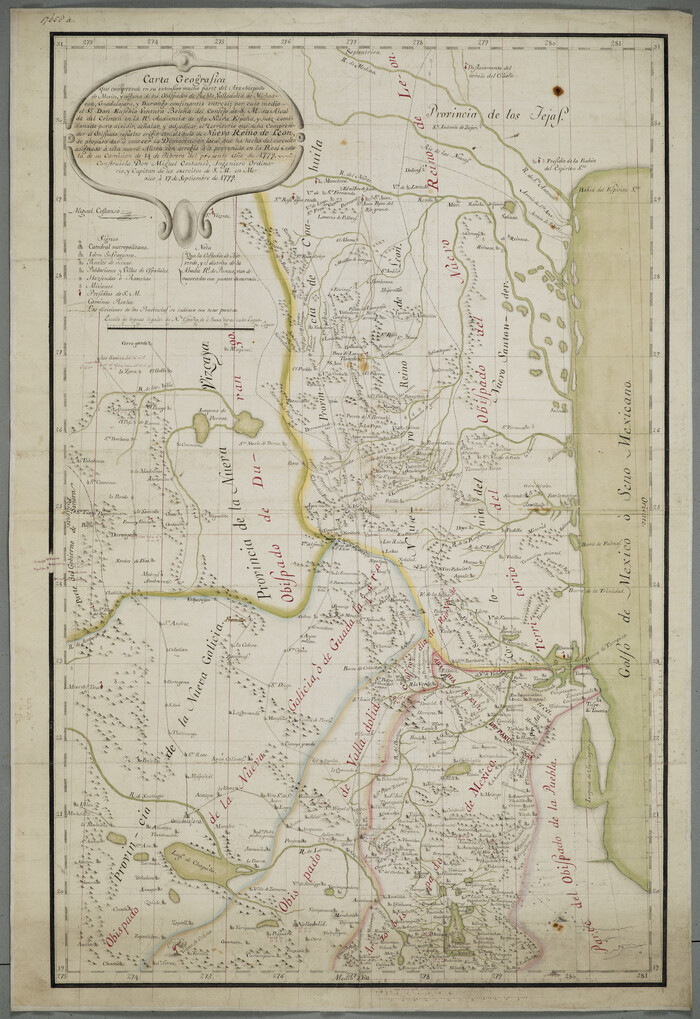

Carta geográfica que comprende en su extensión mucha parte del arzobispado de México, y alguna de los obispados de Puebla, Valladolid de Michoacán, Guadalajara y Durango, confinantes entre si

1779

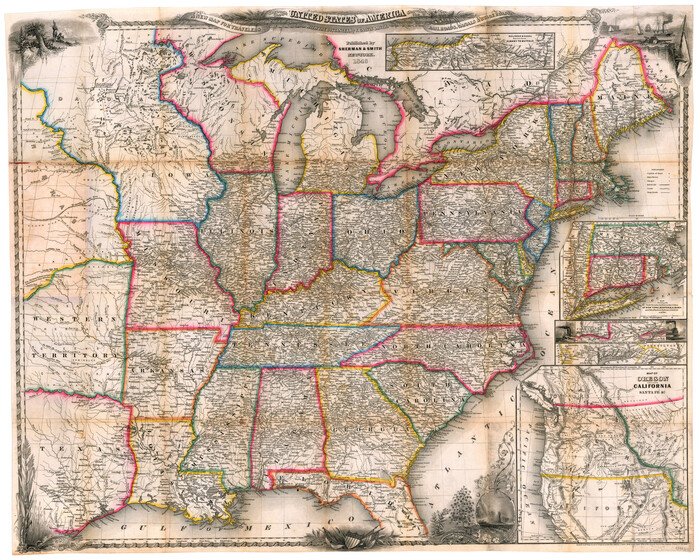

A new map for travellers through the United States of America showing the railroads, canals & stageroads with the distances

1846

The Buffalo Bayou, Brazos and Colorado Railroad (BBB&C)

2022

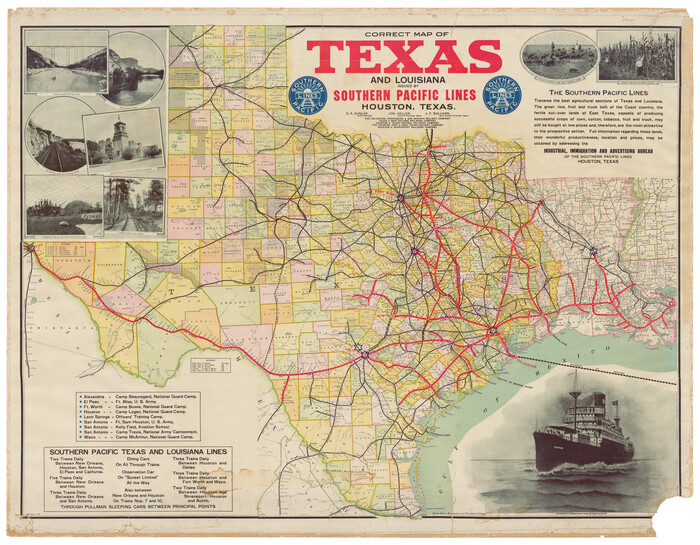

Correct Map of Texas and Louisiana

1917

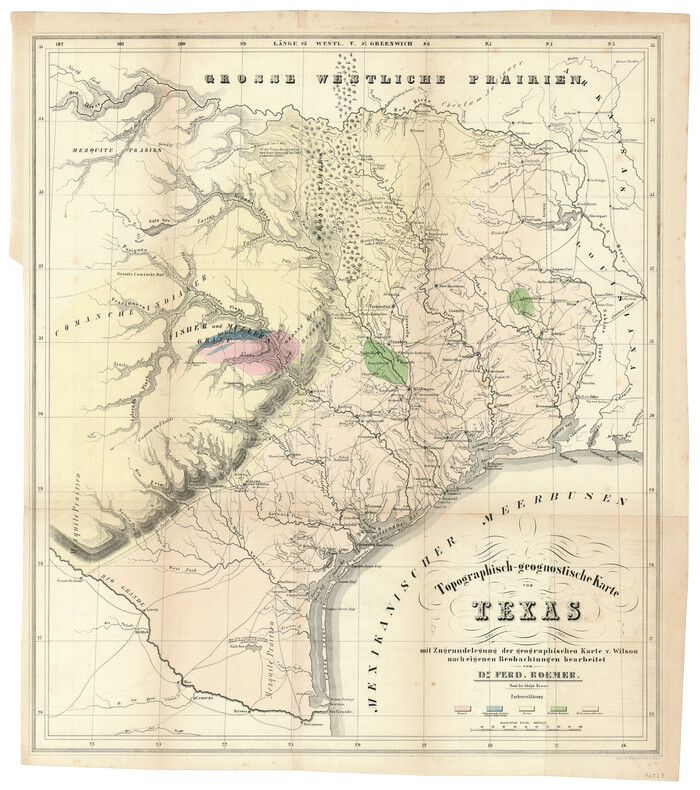

Topographisch-geognostische Karte von Texas mit Zugrundelegung der geographischen Karte v. Wilson nach eigenen Beobachtungen bearbeitet von Dr. Ferd. Roemer

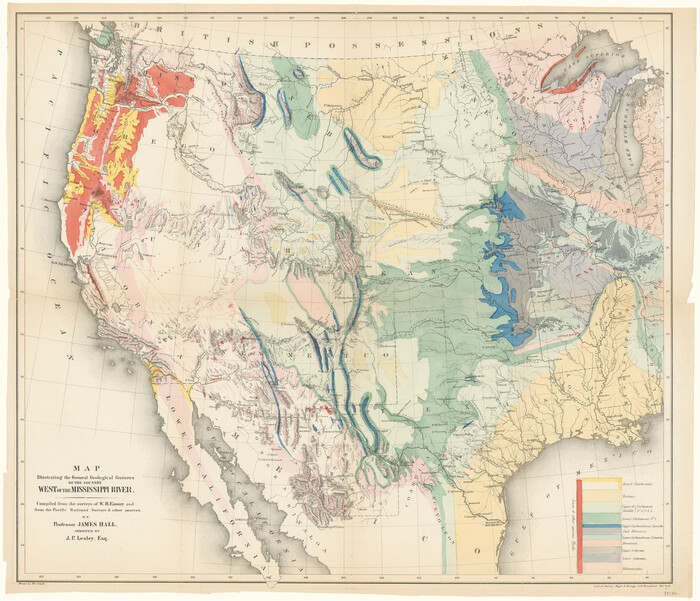

Map illustrating the general geological features of the country west of the Mississippi River compiled from the surveys of W.H. Emory and from the Pacific Railroad surveys & other sources

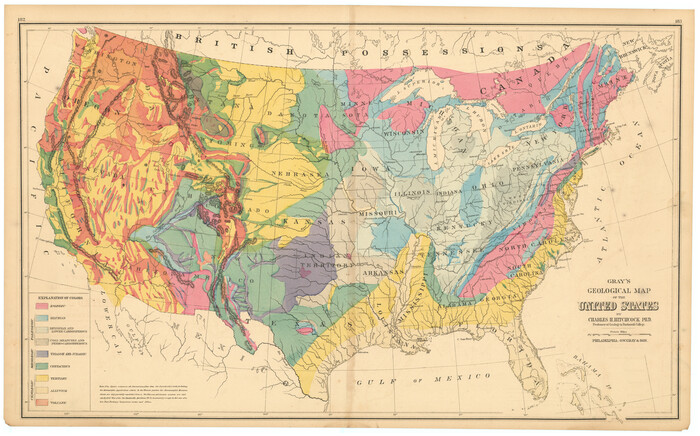

Gray's Geological Map of the United States

1873

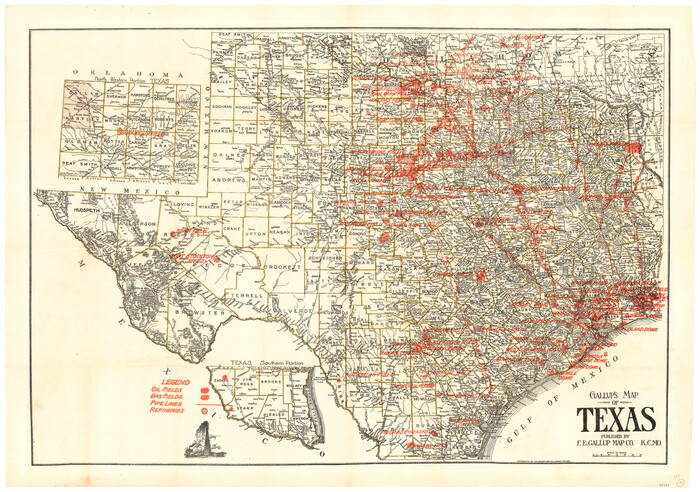

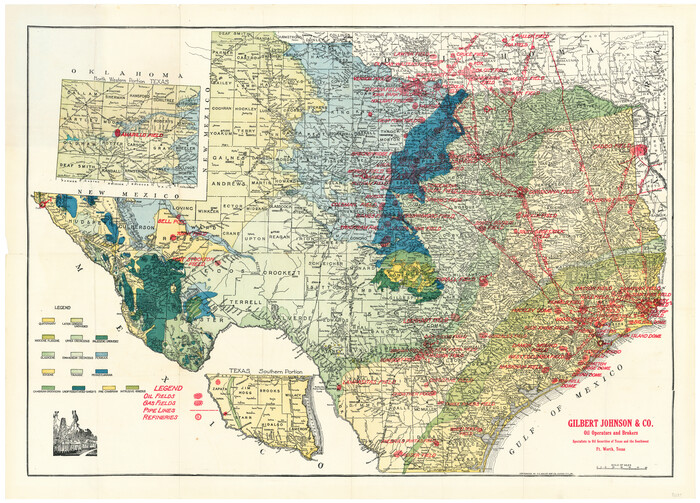

New Oil and Geological Map of Texas showing Oil Fields, Pipe Lines, Refineries, Geological Formations, Etc.

1920